How does the human mind innovate and create using past and present knowledge? What enhances—or impairs—our ability to optimally take advantage of our acquired experience and learning? How can we best promote mental agility to creatively and adaptively meet challenges, and to make the most of opportunities across the lifespan? What cognitive, behavioral, and brain mechanisms are central to an agile mind? My lab, using the diverse and convergent methodologies of cognitive neuroscience, explores these questions focusing particularly on the role of different levels of specificity of representation and varying levels of cognitive control.

Some examples of current and ongoing work in our lab:

- flexible categorization and perceptual interpretation in visual/spatial creative tasks (e.g., the Figural Interpretation Quest or FIQ), see Koutstaal (2025), A new test for assessing creative flexibility of perceptual interpretation

- dynamic processes of creative ideation and problem-solving assessed by Self-Guided Transitions or SGTs, see Koutstaal (2025), Self-guided transitions and creative idea search

- curiosity, question asking, and creative ideation; see Koutstaal et al. (2022), Capturing, clarifying, and consolidating the curiosity-creativity connection

- creative arts interventions for adolescents and assessment of cognitive, neural, and behavioral changes (collaboration with Dr. Kathryn Cullen, Dept. of Psychiatry), see Yue et al. (2025), Capturing creative imagination in the adolescent brain

- technological interventions in adaptive problem-solving, e.g., digital conversational assistants, see Ferland et al. (2025), Deliberate positivity as a promising strategy for conversational agents

The iCASA Framework

(Koutstaal, The Agile Mind, 2012. New York: Oxford University Press)

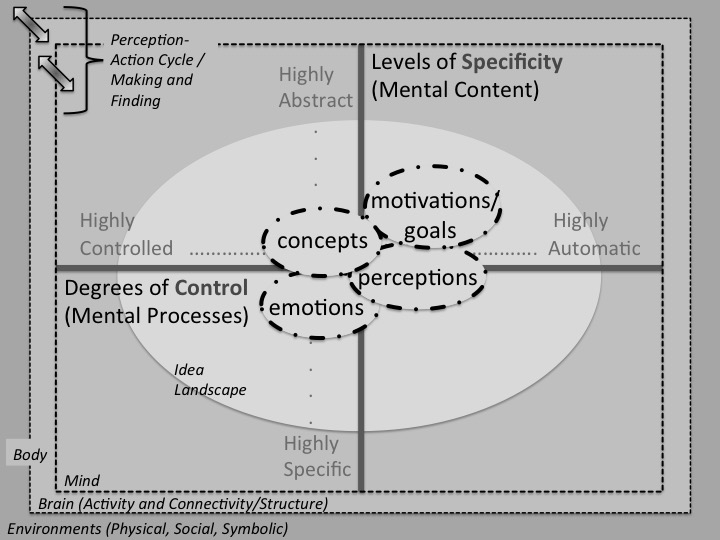

I have developed the integrated Controlled-Automatic, Specific-Abstract (iCASA) framework for conceptualizing the processes and representations that contribute to agile thinking. Although thinking clearly does involve concepts and memory, thinking is intimately interconnected with our goals and actions, emotions, perceptions, and our physical and symbolic environment. And at the dynamic interface of these all is our brain.

In this framework, a central requirement for optimal mental agility is the ability to show what I call “oscillatory range” in both our levels of representational specificity, and our degrees of cognitive control. When we are mentally agile, we are able to adaptively move between highly deliberate and intentional modes of control, to more spontaneous, to more automatic forms of control as circumstances change and in accordance with our goals. We are also able to flexibly move between representations that are extremely abstract or general to representations that are specific, without becoming “constrained” to overly abstract or excessively detailed construals of the situation.

The iCASA framework builds on the strengths of dual-process accounts of cognition that bifurcate modes of thinking into two classes, such as an “Intuition” vs. “Reasoning” system, or “System 1” vs. “System 2.” However, the iCASA framework addresses significant limitations of those accounts by explicitly recognizing continuous variation (gradations) in both levels of representational specificity (LoS) and degrees of cognitive control (DoC) — in not only concepts or memory, but also in our representations of goals and actions, perceptions, and emotions. The iCASA framework also emphasizes the intimate reciprocal influence of our symbolic, physical, and social-emotional environment on the mind-brain. The environment, broadly conceived, is continually and dynamically altering our LoS and DoC at multiple time-scales and at multiple levels—in an ongoing process of “making and finding.”

Distinguishing Mental Agility

Mental agility is related to many further concepts, such as creativity, self-regulation, executive function, fluid intelligence, and resilience. However, whereas each of these constructs prototypically emphasizes a particular end of the degrees of control and/or levels of specificity continuum (for example, executive function is very closely tied to controlled processing), mental agility is a broader, more encompassing construct. Research on mental agility focuses on the factors and conditions that enable us to adaptively and creatively modulate the degree of cognitive control that we demonstrate, and also to aptly and effectively adjust the level of representational specificity with which we conceive problems and respond to challenges and opportunities.

THINKING LAB

Wilma Koutstaal

S512-S517 Elliott Hall, Department of Psychology

University of Minnesota

75 East River Road

Minneapolis, MN 55455; Lab Telephone: 612-626-2174

STUDENTS

Students interested in conducting research in our lab, including undergraduate Directed Research Projects, or the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP), should contact me via email (kouts003@umn.edu).

LAB RESEARCH

In our lab, we examine processes and factors that may either enhance, or impede, our ability to think in flexibly adaptive ways.

Experimental cognitive psychology research is conducted with various participant populations. Our lab also uses neuroimaging techniques (fMRI) to examine the neuroanatomical correlates of flexible thinking and imagination.